Although overall economic benefits from the deal seemed to be negligible, India might have just missed an opportunity to emerge as a key player in the largest trading bloc outside WTO.

Ever since Prime Minister Modi announced India’s decision to pull out from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement, there has been a lot of debate on the merit of this deal for India.

To be sure, the RCEP negotiations have neither been completely favourable to India nor has New Delhi been able to emerge as a leader in the deal-making process. Also, Indian negotiators have persisted for seven long years – five years under the current dispensation – before deciding to pull out. However, it is also pertinent to note that being part of rules-making negotiation process from the inception till the end would have automatically conferred India a huge say in the deal, a privilege which the country has foregone by moving out. By leaving the discussion table, New Delhi might have also lost the moral and strategic power to partake in the rules-making process at a later stage.

So, what are the pros and cons of moving out of the RCEP deal and how do they stack up?

Why staying away from RCEP makes sense

First, various economic models that analysed the correlation between RCEP and India’s economic growth show not so subtle gains from RCEP. Particularly significant is the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP), a multi-country, multi-sector model developed by Purdue University. The study indicates that in the face of protectionism following the US-China trade war, India’s gains from the RCEP deal would be a 0.97% boost to the GDP, a 1.22% rise in investments, and a 0.73% spike in consumption growth. The report of High Level Advisory Group constituted by the Department of Commerce, Government of India, with the objective of assessing the global scenario and giving recommendations, however, favoured RCEP and outlined its positive economic benefits.

Second, certain individual sectors, too, might be adversely impacted if India becomes a part of the deal. For instance, from our own GTAP-based research studies, it can be inferred that specific sectors like automobiles, which are going through stressful times, may face losses due to RCEP-related tariff reductions, which might result in increased imports of automobile parts. One may argue that such potential losses have been averted by withdrawal from RCEP.

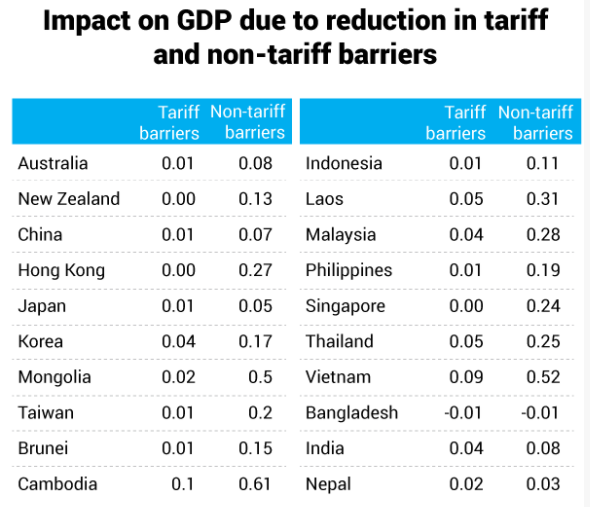

Third, a study conducted (by the authors of this article) on the effect of RCEP on various macroeconomic and sectoral variables, focusing on tariff and non-tariff barrier (NTBs) reductions, too, showed only a marginal impact. Though NTBs are not a part of the RCEP negotiations, this was included in the study to get as optimal a view of the impact of RCEP as possible, from an economic standpoint. Usually reductions in NTBs result in a much higher impact than those from tariff reductions. The analysis shows that while other countries in the Asia-Pacific region stand to gain from RCEP, the positive effect on India’s GDP is marginal, for both tariffs barrier reductions (0.04%) and NTB reductions (0.08%).

Fourth, India runs a trade deficit with 11 of the 15 RCEP partners, the highest being with China. Critics say staying in the deal would have made the Indian market susceptible to dumping of cheap Chinese-manufactured goods. In FY19, 34% of India’s imports were from the RCEP member countries, while exports were 21%. With regard to the commodity-wise imports and exports to the RCEP belt, India runs a trade surplus in agriculture and allied products, readymade garments, and gems and jewellery. Critics of the deal say opting out is the right decision, as whatever trade surplus India runs with the region in the above items could also turn into deficit post its inclusion in RCEP. There are also concerns about challenges (read imports) from Singapore, Australia, and New Zealand. This would only accentuate and widen India’s trade deficit.

There could be potential gains if some RCEP members separately negotiate bilateral trade deals with India, thereby increasing the country’s strategic importance as a trading partner.

However, there are several reasons being put forward for being a part of RCEP.

What India could gain from the deal

First, geopolitically and strategically, India had a great opportunity to become a global leader by integrating with the largest value chains across the world and thus emerge as a global manufacturing hub. This would have provided a booster dose to growth and employment opportunities, lead to higher living standards, and enhance efficiency inevitably associated with any trade deal. Despite such visible gains, India decided not to pursue the deal, citing absence of ‘trade reciprocity’ which implies granting mutual concessions in tariff rates, quotas, or other commercial restrictions, a terminology now often used by the Donald Trump administration.

Second, domestic reforms, better infrastructure, and efficiency improvements to strengthen the local players are a prerequisite to liberalising markets, the absence of which negates some of the gains from trade liberalisation. Reforms in terms of lower costs of energy and electricity, credit and capital, and lower corporate taxes to keep the industry competitive are a prerequisite to benefit sufficiently from the deal even in the scenario of adverse terms of trade. To a certain extent, India is feeling the heat of competition and cheaper imports due to the competitive disadvantage of domestic players, which is attributable to low productivity. If these issues are sorted out, entering the RCEP could be beneficial, supporters of the deal believe.

Third, though some sectors might be adversely impacted, it is equally true that there will be broader gains to the consumers, as they benefit from potentially cheaper imports. Some producers may also gain from cheaper imports to the extent that they consume intermediate inputs that are imported. Moreover, competition would force local players to innovate and achieve productivity gains which would have a multiplier effect in the long run. Also, such mega trade deals may help open up new venues for Indian exporters.

Fourth, supporters of the deal say India’s entry into the RCEP will help diminish the clout of China and make the ASEAN a more equitable trading bloc.

Finally, the pro-RCEP-entry camp argues that staying out of the grouping implies favoring sub-optimally efficient firms vis-à-vis the efficient producers and the consumers which creates an adverse selection problem. They say India should first facilitate efficiency improvements from a macro and sectoral perspective and then jump into the deal with greater bargaining power, with renewed confidence of being in a much more competitive situation. So, in short, under the current circumstances, it wouldn’t be wrong to state that we were constrained to opt out due to lack of domestic competitiveness. As stated earlier, if productivity of the domestic industries is restored, India can still enter the RCEP at a later stage, of course with a lower clout as the deal is likely to be more skewed in favour of countries like China.

The bottom line

RCEP is perceived to be the largest trade deal outside the World Trade Organization (WTO). Now that India has opted out, there is even a possibility that this pact may not be the largest anymore. The developed-country bloc had its eyes on India’s huge market of 1.3 billion populace. India’s exit could disappoint this group and the member countries on the whole might end up not gaining much from an RCEP minus India.

Meanwhile, India’s decision to opt out may turn out to be a blessing in disguise. The country still has an opportunity to bargain hard on ‘trade-reciprocity’ measures since the deal is to be inked only by February 2020. Opting out could also indicate India’s resolve to sign potential deals independently with RCEP member countries.

In the light of the above arguments, it would be an extremely intricate task to precisely state the outcome of the deal for India.

To conclude, though overall economic benefits from the deal seem to be negligible, broad sectoral losses by staying away from the deal could be big. Most importantly, India might have just missed an opportunity in terms of strategic positioning to emerge as a key player in the largest trading bloc outside WTO.

(Badri Narayanan is founder Infinite-Sum Modelling, Seattle, former McKinsey economist, and affiliate faculty member, University of Washington Seattle.)

(Somya Mathur is senior economist at Infinite-Sum Modelling and Indian School of Political Economy, Pune.)

The article was originally published in The Economic Times.