Sukhmani Kaur Toor and Badri Narayanan Gopalakrishnan

For the economy, the policy is a clear move towards achieving green recovery in the post-Covid era. This makes India one of the very few developing nations which have taken tangible measures towards sustainable development in the automobile industry. For an average Indian, this calls for some cost-benefit analysis before heading onto their vehicle’s 15thanniversary. The scrappage incentives can only result in a mild uptick in sales of EVs in the short run as ICE vehicles and alternative fuel vehicles retain their edge.

India’s vehicle scrappage policy introduced in the 2021 budget session aims at replacing end-of-life vehicles (ELV) by granting incentives for scrappage or disincentives for retaining them.

Apart from ensuring that inefficient and polluting vehicles are retired, it also embarks on an ambitious formalisation of the scrappage industry. Under the policy, scrap value of ELV is fixed at 4%-6% of the ex-showroom price of the new purchase. Owners of personal vehicles older than 20 years and commercial vehicles older than 15 years must bid farewell to their rides, if found unfit. Even to retain personal vehicles older than 15 years is possible, but at a price. Electric vehicles (EVs) are exempt from paying a green tax, proposed for personal vehicles at the time of re-registration. Green tax is already applicable in some cities, but this is now set to be levied nationwide with differing rates, with highly polluted cities going up to as much as 50% of the road tax.

For the economy, the policy is a clear move towards achieving green recovery in the post-Covid era. This makes India one of the very few developing nations which have taken tangible measures towards sustainable development in the automobile industry. For an average Indian, this calls for some cost-benefit analysis before heading onto their vehicle’s 15thanniversary.

Compared to EVs, ICE vehicles have the advantage of being tried and tested. Moreover, they are cheaper at the time of purchase. Exemption of electric vehicles and strong hybrids from additional taxes and fees does seem like a strong stimulator of EV demand. But similar exemption of alternative fuel vehicles dampens the potential rise in EV sales.Sukhmani Kaur Toor and Badri Narayanan Gopalakrishnan

India features among the top 10 automobile producers in the world – a testimony to the current and potential capacity of the sector. It is therefore insightful to analyse India’s position relative to the world’s leading producers of automobiles. In terms of size of the auto sector, India is a strong contender among countries such as Germany, USA, the UK, Canada, France, as well as some of the Nordic countries. However, when the sector is disaggregated into various segments notable differences emerge with important takeaways for India.

By some independent estimates, up to 80% of the Indian EV market is dominated by two-wheelers. The share of affordable four wheelers is only a little over 10%. The remaining are small shares of heavy-duty commercial vehicles and luxury cars. This is in sharp contrast with other countries, where the two/three-wheeler segment is relatively less dominant.

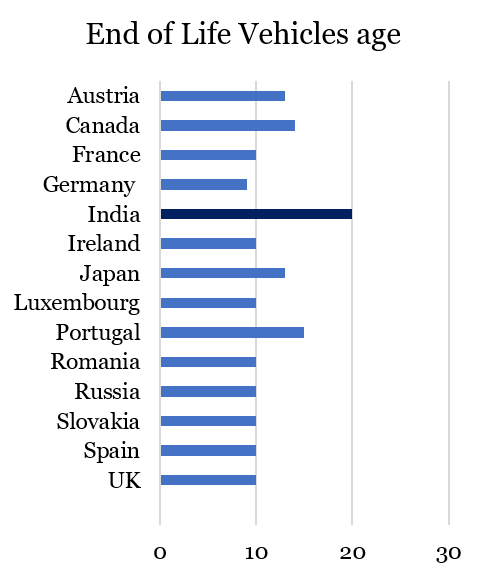

Many of these countries introduced temporary scrappage policies in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, as a step towards economic recovery.The typical lifespan of the old vehicle was fixed at around 9-10 years after which it qualifies for scrappage benefits.This is considerably less than the upper limit proposed in India – 15 years with a possibility of re-registration to extend the life of personal vehicles for another 5 years.

While the age of vehicles is a common criterion, other criteria such as distance covered, and emissions requirement are also used widely. It is worth noting that countries such as Italy and France provide scrappage incentives for vehicles over 10 years of age as well as have an emissions criterion. Notably, these countries have demonstrated a strong and steadily rising presence of electric vehicles over the decade following introduction of scrappage policies.

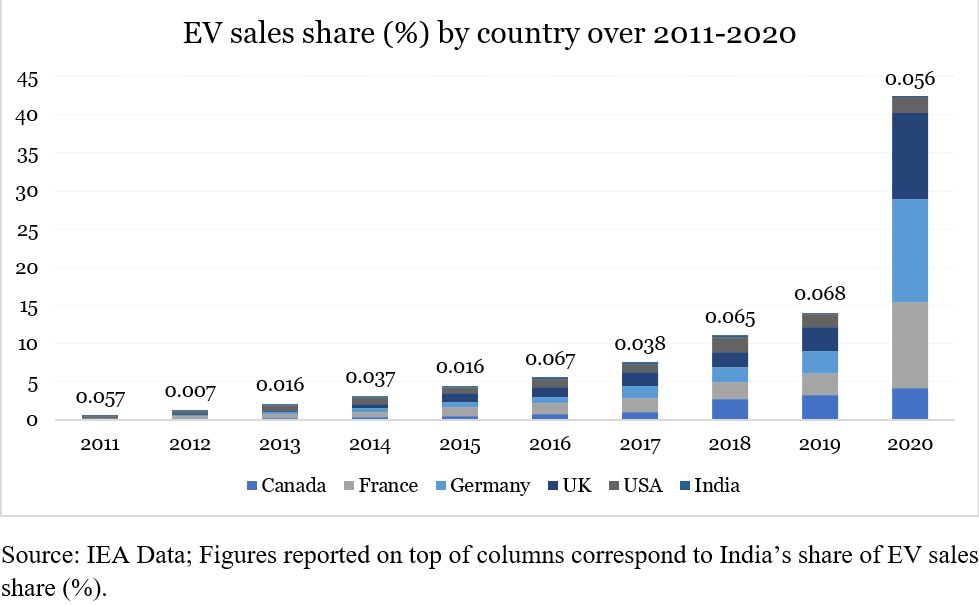

Contrary to countries such as Canada, France, Germany, the UK, and USA where shares of EV sales (%) have risen consistently over the period 2011-2020, the corresponding figures for India are not particularly encouraging. According to the Global EV Outlook 2020 published by International Energy Agency (IEA), the market penetration of electric cars in India has been low, not more than 0.1% during 2005-2019.

This begs the question – what does the scrappage policy really mean for the Indian EV market? Does it aid a sustainable transition from ICE to EV? Here is what one must consider. Stock market response to the policy announcement affirmed that it is well received by the Indian auto sector.

Shares of M&M reportedly rose by 6%, followed by other key players. Industry experts are optimistic about their new car sales predictions based on simple economics. As people move away from older vehicles, the result is an uptake in new ones. Rebates and concessions again work towards this end. While it is reasonable to expect that demand for EV increases, it may not be the case due to availability of a close substitute- ICE vehicles. Compared to EVs, ICE vehicles have the advantage of being tried and tested. Moreover, they are cheaper at the time of purchase. Exemption of electric vehicles and strong hybrids from additional taxes and fees does seem like a strong stimulator of EV demand. But similar exemption of alternative fuel vehicles dampens the potential rise in EV sales. Out of new sales, two-wheelers and three-wheelers are still likely to remain dominant given their popularity and cost effectiveness. However, demand for electric four-wheelers may remain subdued.

Another aspect of the policy is concerned with the states’ approval. Allowing road tax concessions of up to 15% and 25% for commercial and personal vehicles respectively is a longshot, especially for fiscally strained states. Similarly, green taxes may not be uniformly applied to all states. As such, exempting EVs from additional tax loses value if a state does not charge it for conventional vehicles. Such variability leaves the future market trend for EVs at the mercy of consumer preferences and behavioural tendencies, which take their sweet time to change. Thirdly, note that even when OEMs provide discounts and lucrative rebates on new EV sales, it might translate into price hike as a compensatory move to maintain markup.

Italy and France provide scrappage incentives for vehicles over 10 years of age as well as have an emissions criterion. Notably, these countries have demonstrated a strong and steadily rising presence of electric vehicles over the decade following introduction of scrappage policies.Sukhmani Kaur Toor & Badri Narayanan Gopalakrishnan

To summarize, scrappage incentives can only result in mild uptick in sales of EV in the short run as ICE vehicles and alternative fuel vehicles retain their edge. The segment-wise breakup in the EV industry is also likely to continue. However, there is a strong rationale behind anticipating steady growth in various segments in years to come. The correlational analysis of countries earlier also points towards this. This will be made possible by multiple complementary factors evolving in the Indian EV ecosystem.

The FAME 2 scheme is an important policy in this regard. To account for a more balanced transition towards EV, over 40% of the total outlay is earmarked for electrification of buses, the remaining being allocated to 2 and 3-wheelers and plug-in hybrids. With demand-oriented scrappage incentives and supply-side leaning FAME2, a gradual alignment of the two policies will result in the desired upward trend in EV.

Meanwhile, deficits in the charging infrastructure for plug-in hybrids are bound to reverse gradually. Together, these factors can ensure that EV adoption in India changes gears. However, going full throttle on EV adoption needs rigorous actions on some other missing elements such as incentives to invest in the industry, and the entire supply chain ecosystem, as we have argued in one of our previous articles.

Disclaimer: Sukhmani Toor is a researcher at Infinite Sum Modelling LLC, Seattle. Badri Narayanan Gopalakrishnan is the founder of Infinite Sum Modelling LLC, Seattle. Views expressed are their own.

This article was originally published in Economic Timeshttps://auto.economictimes.indiatimes.com/